Fandom is a tricky thing. I’ve been a fan of many things for as long as I can remember. The first fandom I truly fell into as an all-consuming, make-it-my-whole-personality way was probably the Wizard of Oz (books ONLY thank you). My tween years were filled with reading all the Oz books and writing about them, drawing about them, exchanging letters with the extraordinarily patient head of the International Wizard of Oz club over the course of a few years (always very polite, gently indulgent, never inappropriate), and collecting things related to Oz. I liked the movie well enough, but it wasn’t right. It wasn’t the Oz or Dorothy of the books and for me it was all about the books.

I went through major and lesser fandom fits over the next many years — M*A*S*H (embarrassingly in love with Hawkeye Pierce), the original Battlestar Galactica (Apollo!!); Lou Grant (look, I was a weird kid); the original Star Trek (in reruns); Duran Duran; Fleetwood Mac and Stevie Nicks.

By the time we get to the Monkees revival in the 80s, my fandom burned hot. All my fandoms combined with research. I would dig up everything I could find about my new passion and in those days, that meant hours in the library. It was easier with the Monkees because I worked at the library, and digging through old magazines for articles and interviews from the late 1960s was very easy to do on breaks. I collected magazines and posters and albums and photos, went to concerts, spent hours watching episodes, talking about the Monkees with fellow-fan friends, and writing fanfiction — all before the dawn of the graphical internet. Around this time I had a lesser but still very important Beatles phase and also first fell in love with Doctor Who via reruns on WTTW (Chicago’s PBS station).

Next came U2, and I would haunt the record store for special editions, imports, posters, etc. Only saw them once in concert but it was the Joshua Tree tour — a highlight of my college years — on November 1, 1987 in Indianapolis. And I was fairly fortunate in my fandoms — no huge disappointments aside from things like the too-early cancellation of a show I loved or the breakup of a band.

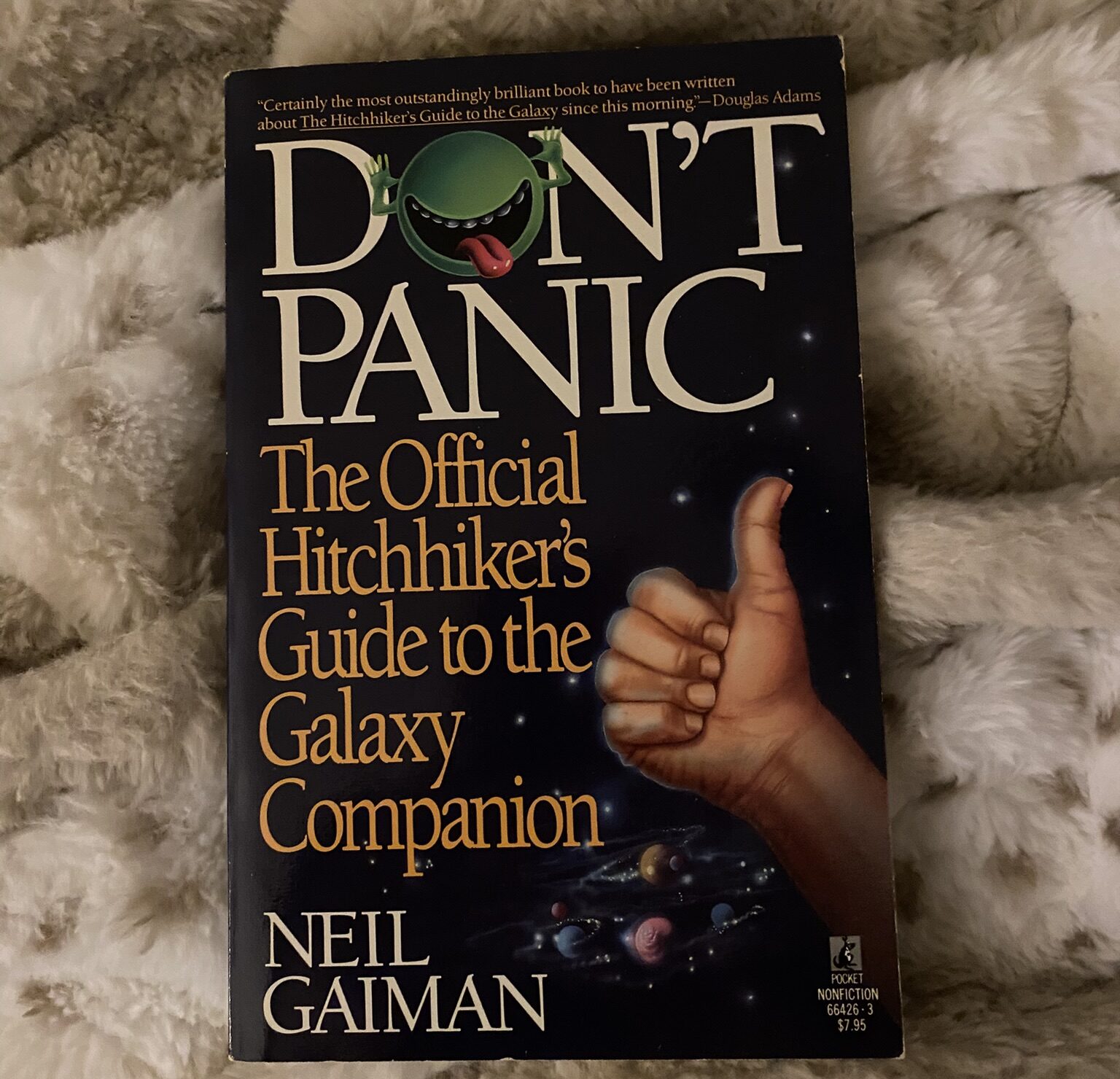

This was a pretty rich time for me and fandom. There were so many things to love, and I loved so many things. And it was also the era when I first encountered Neil Gaiman’s work — not via comics but in the book Don’t Panic: The Official Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Companion — also a big fan of THAT— books, radio show, TV show — all of it. This was how I first knew him, as someone who did fandom overview books.

I missed reading Sandman in real time as I didn’t get into comics until early 1998, but once I did, I caught up with it, and it was a series I truly loved. I loved Death and Delirium; I loved some of the art (especially all the related work by Jill Thompson and Mark Buckingham) and all the Endless. I bought trades and t-shirts, statues and art books and eventually the Absolute Sandman four-volume set and Absolute Death doorstop as well. I loved Neverwhere and The Graveyard Book, liked Coraline and American Gods, but was left a bit cold by Stardust and bounced off Anansi Boys a couple of times. I never read Good Omens or any of his other novels. I didn’t find much of his post-Sandman comic-but-Sandman-related work very engaging, but some of it was good.

I met Gaiman a few times, very briefly, at signings. He seemed nice and gracious, but I was always a bit uncomfortable with how for-granted he took his popularity in that little comics pond — an expectation of adulation. Very off-putting to me.

I think a lot of small-pond-famous people get a bit too used to acclaim and there is this air of condescension that hovers — “of course all the little people must have their moment with me” — He was like that, and I felt bad at the time for feeling that it was kind of icky that he was like that.

Finally, for me and my considering him a person of whom I was a fan (versus being a fan of just some of his work), I will only vaguely wave toward an incident that happened to someone I know — and it was nothing like what’s been written about elsewhere in recent days. It was just an interaction (or in this case a complete lack of interaction when there should have been some for basic politeness’ sake) that underscored my existing unease with what I’d long felt was a very performative aspect of his treatment of his fans, and since that moment (in the earlier 2000s), I cooled on him. I still liked him, but the fandom feelings were entirely gone.

He was a fixture in the upper Midwest for many many years — living vaguely north-ish westi-sh but not that far-ish from where I was for much of his Not Really That Famous years. Throughout this time, he blogged, he Tumblr’d, he talked about possible adaptations of his works that never happened, he schmoozed, he name-dropped, he sooper-sekrit-projeckt’d (barf).

Eventually he met his future ex-wife Amanda Palmer, his youngest-at-the-time graduated high school, and his Midwest rural country squire era came to an end.

And at some point after that, he finally got More Famous — a thing I am absolutely convinced he’d been desperately trying to achieve since he was writing fandom guidebooks in the 80s.

I don’t have any insight. I fully believe all the stories, and in a way, I am not surprised at all to learn he took advantage. What’s shocking to me is just how criminal his taking-advantage was, how abusive, how cruel. When you are a certain type of person, and you’re famous or rich or good-looking or all of the above, with access to adoring fans aplenty, a bit of effort could easily make whatever experience ensued a great one for all involved.

But that wasn’t what he was after. And I think what’s so upsetting as these stories come out about him and come up again and again at various levels of bad with various bad actors is that this never seems to be what they’re after.

These abusers want to be abusive. There is literally no other reason for it to happen. Enthusiastic consent from excited fans or people who just thought he was hot was absolutely accessible to him.

But that isn’t what he wanted.

And that just corrodes everything he ever touched.

The fallout for someone like me is trivial in comparison with his direct victims but he’s yet one more disappointment in an apparent sea of grasping, selfish users who’ve weaponized their main character syndrome.

As with JKR, I now have stuff I don’t know what to do with. Some I may be able to still enjoy — the statues designed by artists whose work I love I think won’t bother me, at least I think that now. But with JKR, things I thought I could keep and still value eventually all went. If I have anything left, it’s more due to not wanting to discard a gift. I will at some point do just that.

As with JKR, I now have stuff I don’t know what to do with. Some I may be able to still enjoy — the statues designed by artists whose work I love I think won’t bother me, at least I think that now. But with JKR, things I thought I could keep and still value eventually all went. If I have anything left, it’s more due to not wanting to discard a gift. I will at some point do just that.

But the books are corroded. Much like with Speaker for the Dead by Orson Scott Card, when you find out the person who wrote what seemed such an insightful understanding of the humanity and value of the other is an unreconstructed homophobe — what do you do with that?

In this case, how do you reconcile a man who commits horrific sexual assault with a man who wrote so seemingly movingly about the horrors of sexual assault?

I can’t. And what this understanding does is shift my entire literary analysis of his body of work, because instead of seeing, for instance, a man who understood Calliope’s plight, I know now that he did not understand her at all — he understood her abuser.

It changes everything about how I would read every aspect of his storytelling. And I don’t want to read his stories with this new understanding. Just as I don’t want to read JKR’s or OSC’s now that I know who they really are.

I do not need artists to be paragons, but I do need them to not be abusers.

Why does that feel like such a big ask?